Wanting to look ahead to the summer and baseball, hopefully?

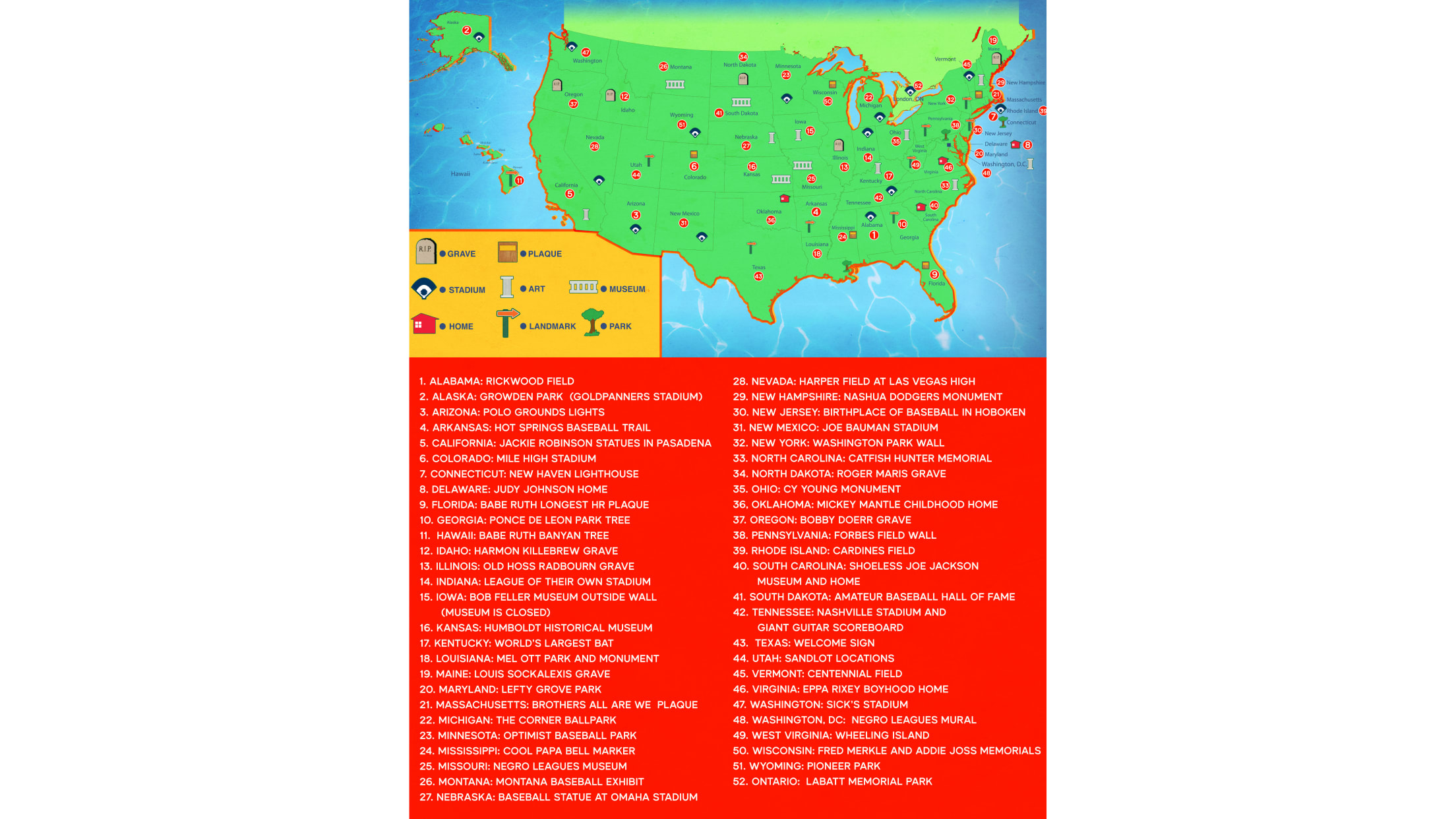

Michael Clair and Dan Cichalski have identified the ultimate: road trip locations in all 50 states:

Baseball road trip locations in all 50 states

Read the entire article by Clair and Cichalski HERE

ALABAMA: Rickwood Field, Birmingham (map)

Known as baseball’s oldest ballpark, Rickwood Field opened its doors on Aug. 18, 1910. It was such a big deal, the entire city took the day off to commemorate it. Since then, dozens of Hall of Famers have played there, including Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson, Babe Ruth, Willie Mays and George “Mule” Suttles.

While we still don’t know about any events being held there this year, you should still be able to get a selfie in front of its famous entrance.

ALASKA: Growden Park, Fairbanks (map)

While they missed it last year, it’s coming back this summer: Get ready for the annual Midnight Sun Game, when teams meet up to play in the middle of the night with a sky as bright as if it were midday. Should you not be able to get tickets for the June 21 game, you can at least go check out the field where Tom Seaver pitched during the summers of 1964-65.

ARIZONA: Polo Grounds lights, Phoenix (map)

If you want to see an actual part of the Polo Grounds — and not just a refurbished staircase that is all that’s left of the venue — you don’t need to be in New York. Instead, head out to Phoenix Municipal Stadium, where Arizona State University plays baseball.

There, the lights are the same that lit up the Polo Grounds all those decades ago. The craziest part? No one has any idea how they wound up in the desert.

ARKANSAS: Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail, Hot Springs (map)

How much do you know about Hot Springs and its connection to the big leagues? If it’s nothing (like some of us), this trail sets out to make us all smarter.

There are 32 stops on the trail, including the Eastman Hotel, where many teams stayed when they chose the city for Spring Training; hot spots where players hung out in the evening; and plaques honoring some of the game’s all-time greats. There’s even an app to help you navigate your way around.

CALIFORNIA: Jackie and Mack Robinson Memorial, Pasadena (map)

Though he was born in Cairo, Ga., Jackie and his brother, Mack, actually grew up in Pasadena before starring at UCLA. Outside the Pasadena City Hall, you’ll find large sculptures of the two brothers’ heads, with Jackie’s facing toward Brooklyn, where he would go on to become a legend.

Jackie may be the more famous of the two, but Mack was no slouch himself, winning a silver medal in the 200-meter race at the 1936 Olympics — just 0.4 seconds behind some guy named Jesse Owens.

COLORADO: Mile High Stadium, Denver (map)

Mile High Stadium may be most famous for playing host to the NFL’s Broncos, but that wasn’t its purpose when it was built. In fact, it was constructed to house the Denver Bears, who began playing there when the stadium opened its doors in 1948. Thousands of players called the stadium home for a portion of their careers, including Hall of Famers Barry Larkin and Tim Raines plus marvelous Marv Throneberry.

Though the stadium is now long gone, you can find a plaque honoring its history in the north parking lot at Empower Field at Mile High. A marker in the exact location of home plate is roughly 500 feet from the plaque.

CONNECTICUT: Lighthouse Point Park, New Haven (map)

Everyone loves a baseball stadium overlooking the water, thrilling when a baseball lands in the drink in cities like San Francisco or Pittsburgh. It’s shocking, then, that no big league team has decided to incorporate a lighthouse.

That’s not a problem in New Haven, where Lighthouse Point Park — situated on the Long Island Sound — once played host to exhibitions involving big leaguers when there were bans on Sunday baseball nearby.

The park was at its most bustling in 1919, when Babe Ruth and his Red Sox came by, as well as Walter Johnson and a team of All-Stars. The field is long gone, but if you stand at the splash park with the beach behind you, you’re essentially standing in deep right field.

DELAWARE: Judy Johnson’s house, Marshalltown (map)

Johnson was arguably the greatest third baseman in the history of the Negro Leagues. He played 17 years — most notably with the powerful Hilldale Club and Pittsburgh Crawfords — and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1975.

You can still see the place on Kiamensi Ave. he called home with his wife, Anita, from 1934 until shortly before his death in 1989. Though it’s a recently renovated private residence (so please be respectful), there’s a plaque on the corner of the property. For more photo ops, head to a Blue Rocks game at nearby Frawley Stadium in Wilmington, where Johnson’s statue resides.

FLORIDA: Babe Ruth’s longest home run, Tampa (map)

On April 4, 1919, Ruth’s Red Sox faced off against the New York Giants in a preseason game at what was then Tampa’s Plant Field. During that game, Ruth hit what was measured to be a 587-foot home run — the longest of his career.

There is plenty of doubt cast on that number today, but what’s the fun in debunking myths? Instead, check out the site for yourself. A plaque commemorating the moment sits on the University of Tampa’s campus, outside the John Sykes College of Business.

GEORGIA: Ponce de Leon Park’s magnolia tree, Atlanta (map)

Though Ponce de Leon Park — the home of the Southern Association’s Crackers and the Negro American League’s Black Crackers — is no longer there, one famous part of its history still resides in the same place it always has: The center-field magnolia tree. The tree sat some 462 feet from home plate, its branches at times hanging over the outfield, but sluggers Babe Ruth and Eddie Mathews managed to reach it with some historic clouts.

Sadly, no one is hitting homers into it any longer. The tree now sits behind a Whole Foods at Midtown Market and can also be seen along Atlanta’s Beltline, a former railroad bed turned into a mixed-use trail.

HAWAII: Babe Ruth’s Banyan tree, Hilo (map)

Take a drive down Hawaii’s Banyan Drive, and you’ll see some absolutely amazing trees — all planted to honor some of the country’s greats. It’s kind of like Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, done in a more Hawaiian style.

Alongside names like Amelia Earhart and Cecil B. DeMille — who started the practice — sits a tree for George Herman “Babe” Ruth. The tree was planted in 1933 while the Babe was barnstorming in Hawaii.

IDAHO: Harmon Killebrew’s grave, Payette (map)

The mighty slugger, who smashed 573 home runs and led the American League in homers six times en route to induction to the Hall of Fame, has a particularly fitting gravestone, as well. Located in the Riverside Cemetery in Payette — the city where he was born — the tombstone features Killebrew finishing a mighty cut on the front. On the back, it shows a baseball stadium with the phrase, “We’re raising boys, not grass.”

While in town, be sure to take a quick drive down Killebrew Drive on the other side of town, and check out the Harmon Killebrew Miracle Field, which is specifically designed to accommodate individuals with disabilities.

ILLINOIS: Old Hoss Radbourn’s grave, Bloomington (map)

If you want to seek out the final resting place of Hall of Famers, Stew Thornley’s site is indispensable. But for Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn’s grave, all you really need to do is plug in Evergreen Memorial Cemetery to your navigation app of choice and, once inside the cemetery gates, look for Old Hoss himself. In the spring of 2019, a dead oak tree near Radbourn’s grave was carved into a lifesize version of the 19th century pitcher. The inspiration for the pose comes from an Old Judge baseball card — with close attention to detail regarding his left hand.

INDIANA: League Stadium, Huntingburg (map)

Opened in 1894, the field is now home to the Dubois County Bombers — a collegiate summer league team. And while that’s nice if you can catch a game — their season begins June 4 — that’s probably not the chief reason you’re visiting.

No, that’s because it was also the stadium used for the Rockford Peaches in the hit film “A League of Their Own.” The stadium has kept many of the movie’s features, including the vintage advertisements, and quotes from the film dot the walls. So, yes, if you’ve always wanted to give a “There’s no crying in baseball” speech, well, this is where to do it.

IOWA: Bob Feller wall, Van Meter (map)

Feller and his famous fastball were known as the “Heater from Van Meter,” so sure enough, a visit to his hometown is where you’ll want to go to see an impressive brick wall featuring Feller’s face and pitching motion.

Unfortunately, that wall used to be the main entrance to the Bob Feller Museum, but after the pitcher passed away in 2010, interest in the museum faded and it closed its doors in 2014. Fortunately, the building is still in use — it’s now Van Meter’s City Hall. There is also a small exhibit of Feller’s items and memorabilia inside. You can visit Monday to Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

KANSAS: Humboldt Historical Museum, Humboldt (map)

Why make the trip to the Humboldt Historical Museum? Well, there’s early farming equipment, the town’s first jail cell and — oh yeah — the actual bed where Walter Johnson was born. How many museums can claim that?

In addition to the bed and a small display featuring Johnson’s highlights is a display honoring George Sweatt. Sweatt went on to have a successful career in the Negro Leagues with the Kansas City Monarchs and Chicago American Giants, winning three Negro League championships. It is open weekend afternoons June through October, so plan carefully.

KENTUCKY: World’s largest baseball bat, Louisville (map)

Of course the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory would also have the largest baseball bat. It’s impossible to miss, too — the bat leans against the side of the building as if a giant ballplayer had carelessly left it behind.

The museum and factory are opened for tours, but now require advance and timed tickets for entry.

LOUISIANA: Mel Ott Park, Gretna (map)

Ott may have become famous in the big leagues for his power, but he was already well known in his hometown of Gretna as a teenager for his homer-smashing abilities. Long before he hit 511 big league dingers, he was doing it for a variety of semi-pro teams in the city.

Inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1951, Ott received a park named in his honor — and a statue proclaiming him “Gretna’s native son” — in 2009. The park features plenty of open green space, and four baseball fields — two for Little League and two for high school.

MAINE: Louis Sockalexis’ grave, Penobscot Reservation (map)

A Native American of the Penobscot Nation in Maine, Sockalexis is best known to baseball fans as the apocryphal inspiration of the Cleveland Indians’ name. While his 94 career games did come with the Cleveland Spiders from 1897-99, it’s unlikely that the club’s 1915 adoption of the moniker was in tribute to the former outfielder. Upon his death at 42 on Christmas Eve 1913, Sockalexis was buried in a small cemetery within the Penobscot Reservation on Indian Island in the Penobscot River. In the small Old Town Cemetery along Down Street, just over the bridge from Old Town itself, Sockalexis lies beneath two tall trees near the back of the cemetery. His rectangular marker holds a bronze plaque containing two crossed bats and a ball above Sockalexis’ name.

MARYLAND: Lefty Grove Park, Lonaconing (map)

Quite simply one of the coolest — and most extravagant — displays you’ll see for a player on this list. Grove won precisely 300 games in his big league career before returning to Lonaconing every winter until late in his life. Grove was a big supporter of his hometown, providing sporting equipment for the youth baseball leagues and even donating his 1931 MVP Award. You can still see it at the nearby public library.

The city erected this park and statue in Grove’s honor in 2019. Here, you enter through a brick entrance and can stand at home plate to face a figure of Grove, who is depicted just as he releases a baseball. It may not be as good as facing Grove, but you’ve got just about as good a chance of hitting him as you would have when he played.

MASSACHUSETTS: Brothers All Are We, Springfield (map)

In 1934, the Springfield American Legion Post 21 team traveled to North Carolina to play in a tournament to determine the national champion. When they arrived, they were told they could only play if Bunny Taliaferro — the team’s lone Black player — was left off the roster.

The coach asked his team what they would like to do, and the players unanimously voted to leave the tournament and return to Springfield, rather than play without him. There is now a plaque honoring this moment in Springfield’s Forrest Park and a short documentary about the team was also shown at the Hall of Fame in 2019.

MICHIGAN: The Corner Ballpark, Detroit (map)

The site is now officially named The Corner Ballpark after the Detroit PAL raised $20 million to renovate the field, but it may be better known to locals as Ernie Harwell Park. That’s because it’s on the site where old Tiger Stadium stood before the Tigers left for Comerica Park in 2000. While there aren’t many touches of its history that came before, it’s still the same land where Tigers legends like Ty Cobb and Hank Greenberg once played.

If the modern digs aren’t for you, head over to nearby Hamtramck Stadium. It’s one of only five Negro Leagues stadiums still standing. It was only recently rediscovered, too. For years, vines obscured the grandstand and people assumed it was part of a city ballpark fallen to disrepair. Fortunately, the Friends of Hamtramck Stadium have gotten involved and are working to restore it to its former glory.

MINNESOTA: Optimist Baseball Park, Litchfield (map)

The home of the Litchfield Blues – an amateur team playing its home games about 80 minutes west of the Twins’ Target Field – might look like countless other community fields that dot the American countryside. It’s part of a complex featuring seven other baseball and softball fields, plus a hockey arena, all across the street from the high school. But check out the seating behind home plate: No metal bleachers here. Instead, you’ll find numbered stadium seats that once held Braves boosters at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium and Twins fans at the Metrodome. Now that’s some great architectural repurposing!

MISSISSIPPI: Cool Papa Bell marker, Starkville (map)

Perhaps the fastest player ever to play, either by reputation — the legend goes he was able to hit the light switch and jump into bed before the lights went out — or by the numbers, setting the Negro Leagues single-season stolen-base mark with 49, Cool Papa Bell is one of the most celebrated players in Negro Leagues history. You can pay homage by visiting his hometown, where there’s a plaque in his honor at the McKee Park ballfield, located off Lynn Lane.

MISSOURI: Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Kansas City (map)

While COVID-19 forced the museum to change its plans around the 100th anniversary of the Negro Leagues in 2020, there’s no better place to go to celebrate its 101st. Just be sure to check its website for guidelines and protocols, as some exhibits are closed or have been modified to allow for social distancing.

After viewing history, you can get a look at where it all started. Just two blocks away is the Paseo YMCA, the building where Rube Foster established the first Black baseball league in 1920.

MONTANA: Montana baseball exhibit, Billings (map)

After catching a now-independent Billings Mustangs game, it’s time to head over to the Yellowstone County Museum. The Montana Baseball Preservation Society teamed with the museum for a permanent exhibit on the state’s hardball history. Uniforms, gloves, balls and other ephemera are featured, with a particular place of honor for four local American Legion players who went on to the Major Leagues: Jeff Ballard, Joe McIntosh, Dave McNally and Les Rohr. The entrance to the museum is through a restored 1893 cabin moved to its current site at Billings Logan International Airport, so there’s really no excuse not to stop in if you’re passing through.

NEBRASKA: Road to Omaha statue, Omaha (map)

Each June, the best college baseball teams convene upon Omaha to play in the College World Series. It’s basically a two-week (incredibly stressful) party celebrating college baseball. And there is nothing that represents it better than the statue designed by sculptor John Lajba.

It was originally unveiled in 1999 at historic Rosenblatt Stadium, but was moved to the new location of the tournament at TD Ameritrade Park Omaha in 2011.

NEVADA: Harper Field at Las Vegas High, Las Vegas (map)

You want to talk about high expectations? Bryce Harper isn’t even 30 years old and the baseball field at his high school alma mater is already named in his honor. While you may think it’s a bit early to pick up naming rights, it’s not surprising. Harper may have been the most hyped high school athlete this side of LeBron James, appearing on the cover of Sports Illustrated while still playing for LV High.

Even better: some of Harper’s used Marucci bats are part of the entrance gate.

NEW HAMPSHIRE: Nashua Dodgers mural, Nashua (map)

When Jackie Robinson suited up for the Montreal Royals in 1946, he broke organized baseball’s color barrier. But the Nashua Dodgers were the first U.S. team to do it when Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe joined the club the next season. That legacy is honored today with streets named after both ballplayers and a large mural in town featuring the two stars. You can find the mural at 31 West Hollis Street.

Holman Stadium, where the Dodgers once played, is still in use, too, and Newcombe and Campanella’s numbers are retired there.

NEW JERSEY: Elysian Fields, Hoboken (map)

Starting in 1845, the Knickerbocker Club of New York used Elysian Fields, along the Hudson River in Hoboken, for match games of its newly organized baseball team. The sprawling parkland has long been paved over by several blocks in the “Mile Square City” (it’s actually two square miles), but that history has not been forgotten.

The most obvious homage is Elysian Park, a typical urban open space with a basketball court and dog run — but no evidence of baseball. For that, check the Maxwell Place lawn across Frank Sinatra Drive, where a plaque gives a brief history of the “Birthplace of Modern Baseball.” But the biggest commemoration can be found just to the north and west, at the intersection of 11th and Washington Streets. A huge blue home plate with an “H” in the center covers the middle of the roadway, and each of the four corners of the intersection are marked off as bases. Between home and first, on the median dividing 11th Street, sits a bronze plaque mounted on granite denoting the site as the location of the 1846 game between the Knickerbockers and New Yorks. “It is generally conceded that until this time the game was not seriously regarded,” it reads.

NEW MEXICO: Joe Bauman Stadium, Roswell (map)

Though he never got a shot at the big leagues, Bauman was a noted Minor League slugger who topped 50 home runs three times and set a then-professional record with 72 long balls for the Roswell Rockets in 1954. The award for the Minor League leader in home runs every year bears his name.

You can pay homage to this forgotten slugger by visiting Joe Bauman Stadium, home to the Roswell Invaders of the independent Pecos League. There is also a plaque noting his accomplishments at the concessions booth.

Bauman passed away in 2005 and is buried next to his wife in nearby South Park cemetery. You’ll know you’ve found his grave when you see the marker featuring an engraved ballplayer taking a swing.

NEW YORK: Washington Park wall, Brooklyn (map)

Sadly, very little of Brooklyn’s baseball history remains. Ebbets Field was converted into apartments with only a small plaque noting that it was the famous home where the Dodgers played. But before the Dodgers moved into Ebbets (and before they were known as the Dodgers), they played at Washington Park in the nearby Brooklyn neighborhood of Park Slope.

There’s a section of the wall still standing. Located on Third Avenue between 1st and 3rd Streets, you’ll find a white brick wall with no fanfare enclosing a Con Edison lot. If you didn’t know it was once a ballpark, there would be nothing there to let you know.

One word of warning: There is some debate about whether this wall was there when the Dodgers played from 1898-1912, or if it was simply built when the Federal League’s Brooklyn Tip-Tops took over the field in 1914.

Hertford is a tiny town of just over 2,000 people, but that didn’t stop A’s and Yankees Hall of Famer Catfish Hunter from returning every offseason.

As Hertford’s favorite son, Hunter has a memorial in place outside the Perquimans County Courthouse at 128 N. Church Street for you to admire. If that’s not enough, a small Hunter museum is located inside the Chamber of Commerce. Hunter’s gravestone features a large baseball and the A’s and Yankees logos and is located in nearby Cedarwood Cemetery.

North Dakota

Maris may be the most famous ballplayer not in the Hall of Fame. Visit Fargo, and you’d think he was the greatest player in history. This is the town where Maris grew up and starred at Shanley High School. Though he doesn’t hold the MLB single-season home run record anymore, he still holds the school’s record for returning four kickoffs for touchdowns in a single game.

While there’s an impressive Maris museum inside the West Acres Mall, you’ll want to pay your respects to Maris inside the Holy Cross Cemetery. There you’ll find a black diamond tombstone with 61/’61 on it.

Ohio

Cy Young may have been born in Gilmore and buried in Port Washington — complete with a winged baseball tombstone where fans leave baseballs in his honor — but his home was in Newcomerstown. In fact, the city still celebrates him every year with the Cy Young Days Festival. This year it will be held June 25-27, so get your airfare booked now.

That’s also where you’ll find a hometown memorial in his honor at the aptly named Cy Young Memorial Park. A small baseball diamond is laid out next to the real one, with a large stone memorial on the miniature pitcher’s mound.

Oklahoma

Driving into this northeastern Oklahoma town on Route 66, it’s hard to miss the water tower rising above the rooftops: The cylinder is painted with blue pinstripes and a white No. 7 in a blue circle. Commerce is Home of the Tigers — and Mickey Mantle. Stay on the Mother Road and you’ll pass by Mickey Mantle Field at Commerce High, a statue of The Mick in the follow-through of his swing between the center-field fence and the roadway.

But don’t miss the right turn onto C Street, because after a few blocks, at the corner of Quincy Street, sits a small white house and a rusted, leaning corrugated tin shed. The shed served as the backstop for batting practice when Mickey would hit tennis balls pitched by his father and grandfather. One threw left-handed, the other right-, allowing the young boy to work on his switch-hitting.

There are more than 70 former big leaguers buried in Oregon, but only one is in the Hall of Fame.

Born in Los Angeles, Doerr made his life in Oregon, raising cattle after his playing days — which included nine All-Star Games and a .409 average in his lone World Series appearance — were through.

You can find his resting place in Rest Lawn Memorial Park. Unlike the other graves on this list, there is nothing on his tombstone to indicate he was a ballplayer, though, so you’ll need to keep your eyes peeled.

PENNSYLVANIA: Forbes Field wall, Pittsburgh (map)

Roberto Clemente Drive is an apt name for a road that crosses over the plot where The Great One played 1,070 games from 1955-70, even if its path winds from a spot somewhere behind first base out toward left-center field. But anyone driving it today can look over and still see the brick wall that marked the right-center-field boundary of Forbes Field, complete with well-maintained distance numbering and a flag pole that used to be in play. Where the wall ends in what was once center field, a line of bricks continues in the sidewalk, with a plaque embedded at the spot where Yogi Berra looked up and watched Bill Mazeroski’s home run clear the ivy, winning Game 7 and the 1960 World Series for the Pirates. Since 2007, fans have gathered at the wall on Oct. 13 to listen to an original radio broadcast of that game.

RHODE ISLAND: Cardines Field, Newport (map)

Most of the fields on this list were once home to the pros. Big leaguers, future big leaguers, former big leaguers. This one was never really interested in all that as it’s played home to the oldest amateur baseball league in the country. Nestled cozily in the neighborhood, Cardines has all the odd dimensions that being surrounded by residential homes require, with a pub located on the field, too.

Though it’s mostly been used by weekend warriors, a fair share of big league stars have dropped in, too, with Bob Feller, Johnny Pesky, Yogi Berra and Phil Rizzuto among the Cardines alumni. Negro League teams regularly played at the field during barnstorming tours, and Satchel Paige was a frequent player.

SOUTH CAROLINA: Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum and statue, Greenville (map)

To many folks in Greenville, Shoeless Joe Jackson is a Hall of Famer, even if he’s not recognized as such with a plaque in Cooperstown. But he is lovingly remembered at his former home, which was moved from its original location in 2006 to a spot across from Fluor Field, home of the Class A Advanced Greenville Drive. Its address — 356 Field Street — is a nod to Jackson’s lifetime batting average.

In the summer of 2020, the house was moved again (only a few hundred feet this time) to allow for a new mixed-use development called .408 Jackson, in recognition of his 1911 season. The relocation also included an addition and other upgrades, and the attraction reopened in the summer of 2021. You can also visit the statue of Jackson across the street at the entrance to Fluor Field. Joe is shown — with shoes — following through on his swing. The circular base of the statue was made from recycled bricks shipped down from Chicago’s Comiskey Park.

SOUTH DAKOTA: Amateur Baseball Hall of Fame, Lake Norden (map)

If you’re reading this, you’re probably not going to make it into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown as a player. Sorry if that’s bumming you out. Fortunately, there’s a place designed to honor amateur ballplayers in Lake Norden, S.D. The Hall of Fame is located in Salo Hall — 513 Main Avenue — and features memorabilia and photos from more than 100 years of amateur baseball in the region. The Class of 2020 was inducted last August, so it’s quite possible that a new class will be inducted around the same time if you’re making plans.

And if you need a place to stay while in the area, check out the historic Franklin Hotel in Deadwood. Babe Ruth is reported to have once stayed there.

TENNESSEE: First Horizon Park, Nashville (map)

While Justin Timberlake and friends try to bring a Major League team to the city, you can check out this stadium while you wait. First Horizon Park is home to the Nashville Sounds — whose 1970s logo featuring a player swinging a guitar is one of the best ever.

While the stadium is nice, what you really want to see is the large video scoreboard in the shape of a guitar. It’s a little touch like that — combining baseball with the Music City — that really makes this place (excuse the pun) hum.

TEXAS: Welcome sign, Winters (map)

OK, you may think this one is very silly. We’re asking you to drive out to Winters, Texas, to see the sign as you approach Main Street that reads, “Birthplace of Rogers Hornsby.” But bear with us: First, it’s a tiny town of only 2,500, so they have reason to still honor a player born in 1896. And while you’re in town, you can also check out the Z.I. Hale Museum. Along with the second-largest collection of Ledbetter Pressed Glass (could anything be more exciting?), there is, of course, Hornsby memorabilia.

UTAH: Sandlot filming locations, Salt Lake City and Ogden (map)

If you were born any time in the last, oh, let’s say 40 years, “The Sandlot” is probably one of the most important films in your life. Salt Lake City is where you can find the outside of character homes on the 2000 East block, and the pool scenes were shot at the Lorin Farr Community Pool in Ogden. You won’t want to miss the titular location, of course. The sandlot itself is near Glenrose Drive in Salt Lake City. The field was recently brought back to its previous splendor for the film’s 20th anniversary, so it should be ready for your camera to snap a few pics.

VERMONT: Centennial Field, Burlington (map)

Dedicated in 1904, this 4,000-seat ballpark is home to the University of Vermont Catamounts and the Vermont Lake Monsters, who are now a collegiate summer team. Its long history includes several stints housing affiliated clubs, including the Double-A Vermont Reds (1984-87) and Vermont Mariners (1988). Hall of Famers Barry Larkin and Ken Griffey Jr. passed through before they became big league stars.

VIRGINIA: Eppa Rixey’s boyhood home, Culpepper (map)

Born in 1891, Hall of Fame left-hander Eppa Rixey lived in Culpepper until age 11, when his family moved to Charlottesville. Though the front porch may look inviting, it remains a private residence, with a historical marker near the sidewalk presenting a brief history of Rixey’s life.

WASHINGTON: Sick’s Stadium site, Seattle (map)

It might just be the most famous hardware store among baseball history buffs: the Lowe’s Home Improvement center on S. Rainier Avenue in Seattle — a 10-minute drive from T-Mobile Park — sits on the former site of Sick’s Stadium. Once home to the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League and, for just that one 1969 season, the Seattle Pilots of the American League, the ballpark was torn down in 1979. But stop by today, and you’ll find a marker outside the store and a silhouette of a batter standing over the location of home plate in the lumber loading area just to the left of the store exit.

Leading up to the 2018 All-Star Game at Nationals Park, a new mural was unveiled in an alley shared by Ben’s Chili Bowl and the Lincoln Theatre in the District. But it didn’t depict contemporary stars or legends from the Washington Senators; it showed a smiling Mamie “Peanut” Johnson, a D.C. native, and Homestead Grays slugger Josh Gibson, among others. Be sure to get a chili dog to go from Ben’s, a neighborhood institution since 1958.

WEST VIRGINIA: Wheeling Island, Wheeling (map)

Nestled in the Ohio River between West Virginia and Ohio, Wheeling Island can be accessed via a local road from each state or Exit 0 off Interstate 70. Once on the island, there are three spots to acknowledge the Mountain State’s baseball past. Just off I-70 and through the historic district on Zane Street is Bridge Park, with a ballfield that’s been in use since at least the 1950s. Head to the northern tip of the island to visit Belle Isle Park. Now a community field, baseball was played on the site as far back as the 1920s. Unfortunately, Wheeling’s most historic diamond now lies beneath Wheeling Island Stadium (for football) at the southern end. It was here, where a casino and racetrack now stand, that baseball was played on the fairgrounds going back to the 19th century. That included Hall of Famer Sol White, who suited up for the Wheeling Green Stockings for just one season, in 1887, before the Ohio State League banned Black players.

WISCONSIN: Fred Merkle and Addie Joss memorials, Watertown (map)

Fans of the Dead Ball Era can get a double play with a visit to Watertown, about an hour west of Milwaukee. Merkle is infamously known for his eponymous blunder that led to the Giants losing the 1908 NL pennant in a makeup game against the Cubs, but the “fans of Fred Merkle” — including broadcaster Keith Olbermann — note his six World Series appearances and the trust Giants Hall of Fame manager John McGraw had in the young infielder in the plaque designating Fred Merkle Field at Washington Park. Also on the grounds is a memorial to Hall of Fame pitcher Addie Joss, whose career lasted just nine years, cut short by his death at 31 of tubercular meningitis. And a half-mile away, on the grounds of the Octagon House, is a similar memorial for Merkle.

WYOMING: Pioneer Park, Cheyenne (map)

Opened in 1896 as a rodeo arena, Pioneer Park soon became the home of various amateur, semi-pro and professional baseball teams in the rugged Rocky Mountain West. Still in use today by local teams, the field was the home of the 1941 Cheyenne Indians of the Western League. That team’s 59-44 record is the only winning season by a Minor League team based in Wyoming.

**********************************************************************

Know some top athletic performances? Seeing some great teams in action?

We can use your help, and it’s simple. Witness some great performances? Hear about top athletes and top teams in our area?

Nominate an athlete or team: HERE

Pancakes or Waffles! We feature top area athletes with our world-renowned feature. Send us your nominations for who you’d like us to interview HERE

Baked or Fried! We also feature difference makers throughout central Wisconsin: coaches, booster club leaders, adminstration, volunteers, you name it. Send us your nominations for who you’d like us to interview HERE

College Athlete Roundup! We want to recognize student-athletes from the area who are competing at the college level. Send us information on college athletes from the area with our simple form HERE

Where are they Now? We feature athletes and difference makers from the past, standouts in sports who excelled over the years and have moved on. Know of a former athlete, coach or difference maker who we should feature? Know of a former standout competitor whose journey beyond central Wisconsin sports is one we should share? Send us information on athletes and difference makers of the past with our simple form HERE

We welcome your stories! Contact us at news@onfocus.news!

Author: David Keech

David Keech is a retired teacher and works as a sportswriter, sports official and as an educational consultant. He has reported on amateur sports since 2011, known as 'KeechDaVoice.' David can be reached at keechertheteacher@gmail.com